Chapter 1: Structuralism and the Brain

I say "science of God," and yet God is infinitely unknowable. His nature entirely escapes our investigations. He is the absolute principle of being and of beings and must not be confused with the effects he produces; and it can be said, affirming his existence all the while, that he is neither being nor a being. Such a definition confounds reason, without however causing us to go astray, and keeps us forever from all idolatry.

Eliphas Levi, The Book of Splendours

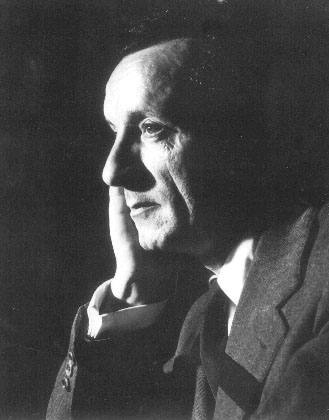

Biogenetic structuralism as a school of thought in anthropology originated in a dialogue between Eugene d'Aquili and myself at a conference in 1972. John Cove, Iain Prattis and I organized the conference at SUNY-Oswego in upstate New York and called it "Theory On the Fringe." That fortuitous event led d'Aquili - then a practicing psychiatrist and anthropology graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania - and myself to get to know each other and to discover that we were interested in the same issues. Among other things, we recognized the fact that the human sciences, and in particular anthropology, were progressing in almost total ignorance of a hundred-plus years of developments in the neurosciences. They were either ignoring the human nervous system altogether (with the exception of some applications in physical anthropology and physiological psychology), or they were treating the human brain as though it were a black box (that is to say, a set of processes about which we know nothing) when in fact we know a great deal about its structures and functions, and are learning more all the time. D'Aquili and I discovered that our relative strengths and weaknesses complemented one another and produced a perspective that could be described in a book. We began writing that book almost immediately and were finished with it by 1973. That book was titled Biogenetic Structuralism and was the first in a long series of papers and books that became the corpus of theory and application upon which I am here endeavoring to reflect from my own particular point of view.

E.G. d'Aquili & Charlie Laughlin in 1973

It has been about fifteen years now since the original collaboration started, and we're still collaborating. We met John McManus in the fall of 1973, only after Biogenetic Structuralism had gone to press, so his input into that first volume was far less than it might otherwise have been. However, collaboration amongst the three of us began immediately on The Spectrum of Ritual (1979), a very complex project that was not finished until 1976. We are presently finishing a lengthy volume together entitled Brain, Symbol and Experience .

We came to understand that biogenetic structuralism was a special case of a kind of structuralism that is rooted in biology, but that is quite unlike most theory that anthropologists code as structuralist (e.g., the work of Claude Levi-Strauss and Roland Barthes). We came to call theory of the latter type "semiotic" structuralism. The type of structuralism to which our work is most akin we have labeled "evolutionary" structuralism. What is structuralism, and why distinguish between the semiotic and evolutionary varieties?

STRUCTURALISM

It is our view that the emergence of structuralism in a science is a mark of its maturity. What do we mean by structuralism in that sense? We mean that observables are explained by reference to non-observed principles -- schemes, operators or structures -- the activities of which produce, perhaps even cause, the observables (see Ackoff and Emery 1972 for the distinction between "cause" and "produce"). Prior to the emergence of a structuralist theory base, a science tends to be pretty much a natural history of observables (see Brown 1963). You collect all the butterflies you find, pin them to cards, and then you try to order them in some way. They all have blue wings, all red wings, or are all big butterflies, medium-sized or little butterflies, butterflies with a black thorax, brown thorax, and so on. This was the state of biology before Darwin, the state of chemistry before the periodic table, and the state of physics before Newton's Principia . This was also the state of anthropology before structuralism. Anthropological theory today has an unsettling, unsatisfying effect upon many of us unless it has some kind of structural underpinning to it, and this is a sure sign of the maturation of the discipline.

This means that in some sense the explanation of observables is by reference to unobserved operations. For semiotic structuralists these unobservables are usually formulated by deduction from abstracted patterns of similarity in observables. Similar patterns in observables lead to the deduction of the structures underlying them and that produce or cause them. So Levi-Strauss likens the relationship between "mechanical models" (or principles of reason) and observables (like patterns of elements and relations in myths or symphonies) to the relationship between the camshaft in a machine that produces jigsaw puzzles and the puzzles themselves. The analyst is no longer interested in the jigsaw puzzles once he has deduced the shape or configuration of the camshaft. It is the task of science to get at the camshaft. In the last volume of Mythologique (1971), he admits that the camshaft must have something to do with the human brain. But a mere admission of relevance is insufficient from our point of view to preclude him being classed as a semiotic structuralist because he only gives lip service to the neurosciences. His theory remains uninformed by the neurosciences and the methodology he uses, which is almost totally deductive from patterns in cultural texts, treats the matter of mind as though the brain itself was not also an observable. In other words, he makes the mistake that Jean Piaget, Earl Count and others do not make, being trained as they were in biology.

Brian Goodwin

Evolutionary structuralism is any structuralism - like Count's (1973) theory of the biogram in anthropology, and Webster and Goodwin's (1982) structuralism and Maturana and Varela's (Varela 1979) autopoiesis in biology - which places the locus of structure in the biology of the organism, however construed. An excellent example is the work of Jean Piaget (1971, 1977, 1980). Piaget never really talked that much about the brain, and when he started his project there was no real way he could get at what he was after by way of the neurosciences as they existed in that day. Nonetheless he was aware that his 'schemes' were biological structures.

Q: By brain you mean the entire nervous system?

A: I'm being sloppy there as usual. When I say "brain" I almost always mean the entire nervous system.

Q: How can you separate the brain from its own functioning?

A: I wouldn't, nor for that matter would any neuroscientist.

Q: So when you're speaking of the mind you are also speaking of the nervous system?

A: Yes. Thank you for this because only in the social sciences, removed as they so often are from biology, will structure be considered apart from function - as Levi-Strauss specifically does. It makes no sense in physiology to talk about structure as distinct from function. They are two aspects of the same process. Of course, you can study anatomy without considering function too much, but no anatomist would say "Well, we'll keep structure and function conceptually distinct." Rather, as anatomists we'll just study it standing still. We've got some corpses, they're not going anywhere, so we're going to cut them up and track this connection, that center, and so on. But in the back of our minds we all know that the anatomical connections have functional corollaries.

Q: Then structure can only make sense because of the function it has to carry out. Otherwise why would it have the structure?

A: Exactly! In modern neo-Darwinian theory you can come to no other conclusion. There is such a thing as latent structures, of course. You can experience that in your own being. I mean, you're not just conditioned by culture to be the age you are now. Wait until you get to your mid-lives. It's all programmed in there waiting for the triggering stimulus events to release them and then they begin to function. So we do recognize latent structures, only they're not really structures without functions.

Q: Could you tell me then if the structure is causally prior to function?

A: No, I will not be trapped so easily into that sort of implied dualism, because there is clear evidence that structures can result from function. One of the failures of semiotic structuralism is that it's almost never developmental in perspective. Its theoretical base doesn't cry out for any developmental processes. The minute you introduce a diachronic dimension to structuralism in biology you immediately have to look at the embryo, watch how the structures are developed from conception through adulthood to death. So evolutionary structuralism tends also to be diachronic, unlike semiotic structural accounts; diachronic either in a developmental frame, or in an evolutionary frame, or both. By the way, Piaget's basic question was not really developmental, it was phylogenetic (Piaget 1970). He wanted to know about the evolution of knowledge, and his primary research strategy was based upon the then current presumption that ontogeny somehow recapitulates phylogeny - a perspective that has lately enjoyed a resurgence of interest (see Gould 1977).

Q: Jacques Lacan, who is also part of the structuralist discipline, is also interested in phylogeny. He talks about transference and, I would say, fundamental reversal of the normal intellectual activity in which the consciousness is engaged. It represents a different desire and, at that moment in the chain of signification, something new is added, and the whole concept of chain of signification is biogenetic, if I'm using the word correctly.

A: Sure. One of the things we try to avoid is the traps constituted by our own conceptual distinctions. It's not easy unless you fundamentally don't believe in any dualism. In these talks I'll use the distinctions, but I don't believe in them. So they don't produce fragmentation of view. The world is always far more complex than we perceive or conceive it to be. As Husserl put it, the world is transcentental whereas we always approach the world from a "horizon." There are an infinity of points of view or "horizons" to any "transcendental" object in the world. None is complete. So, evolutionary structuralism is far more inclusive than just biogenetic structuralism. Biogenetic structuralism is basically on about how much we can integrate information about biological structures with that from behavioural observation and that from direct experience. I'll return to this later, but let me now characterize some other evolutionary structuralist perspectives in case you wish to further explore them.

EVOLUTIONARY STRUCTURALISM

I've mentioned Earl Count. He was trained in the neurosciences and taught anthropology at Hamilton College for his entire career. He's now retired and lives out in the Bay Area. In a sense Count's the father of biogenetic structuralism. I once wrote him a letter to that effect and he wrote back and said, "Oh good. I'm glad it's a boy!" Anyhow, he developed a theory of what he called the biogram . Essentially what he was looking for was the evolutionary anlagen (this is a good German word that doesn't translate well into English, but means something like "ground plan" -- it refers in biology to the structure upon which some future structure is built), the precursor patterns of adaptation to those of the hominid level of human development. To put it another way, if you look at phylogenesis as the emergence of adaptive patterns, what he tries to reconstruct are the precursor patterns at each level of evolutionary remove from the modern human form. So he looked at, say, parenting in humans cross-culturally, then he looked at parenting in chimpanzees, monkeys, generalized primates, insectivores, and so on back, trying to show what was added at each level as it becomes increasingly complexified during the process of evolution. The entire evolutionary process in the hominoid line he calls "homination" (Count 1974). In a sense he succeeds in escaping a lot of concepts like "hominid" and so on, which tend to lump segments of the homination process into some kind of localized~ temporal dimension, as in say the last five million years, the last one million years, or whatever.

Count's works are generally long, rambling essays with no clear systemization. That's what he's struggling with now, trying to formalize the theory of the biogram, but we don't have anything really up to date that he's written. The best source is his Being and Becoming Human (1973), a collection of his essays~ and there are some other essays that have been published more recently (1974, 1976).

Elliott Chapple (1970) is also an anthropologist and was the co-author of Principles of Anthropology with Carleton Coon (1942). They attempted to do an overview of anthropology giving it a biological base. It was mostly unsuccessful, of course, but those of us who are biologically grounded find that work remarkable and inspiring to this very day. Chapple's views are very congenial to a biogenetic structuralist perspective. We drew heavily from him - he liked biogenetic structuralism and we had a lot of dialogue with him at one paint, just as he had over the years with Count. What he tries to show is a biological basis for human sociality, social farms. especially ritual. It is no coincidence that we also turned our minds to the phenomenon of ritual as the first real application of biogenetic structural theory in The Spectrum of Ritual .

Q: Is sociobiology an evolutionary structuralist approach?

Edward O. Wilson

A: Well, in the sense that all real science is fundamentally structuralist -- that is, phenomena are explained in terms of underlying properties or laws that cannot be observed directly in experience. E.O. Wilson (1975) is one of the main proponents of sociobiology. This is truly a reductionist biological formulation, claiming as it does a genetical base for much of what modern anthropologists would want to claim are cultural facts. C.H. Waddington (August 7, 1975 issue of the New York Review of Books ) critiqued Wilson's Sociobiology in the same 1975 review as he critiqued Biogenetic Structuralism . Gene and I were scared to death we would be forever after associated with sociobiology, but fortunately that has not been the case.

Q: Could you say then that biogenetic structuralism's criticism of sociobiology is that the latter is really a kind of reductionism?

A: That's one of our problems with it. In the first place, sociobiology is reductionistic to the genotype. It propounds a naive conception of the genes even from the viewpoint of modern genetic biology. There is really no such thing as a gene. There just isn't a specific gene for a specific behavior. Sociobiologists come off thinking that there are. They make mathematical errors as well. Trivers and others claim that human beings don't share any genetic material if they're not related by blood to each other. They say unrelated humans share zero genes as opposed to siblings who would share much more genetic material. That's just not true, and bad genetics. Their mathematics are all wrong. One of my friends, Tim Perber, a genetic biologist and psychologist, has criticized sociobiology admirably on the inadequacy of their mathematics.

Sociobiology's understanding of the neurosciences is virtually non-existent, or at best inadequate. They seem to have no conception of development at all. There is no developmental frame to sociobiology. The result is a picture of human society that looks suspiciously like a complex colony of ants. And there's really even a developmental aspect to ants. Wilson is one of the world's leading experts on social insects. His rendition of human sociality gets tacked on at the end of Sociobiology and makes it appear that he's applying entomology to anthropology. His scheme just doesn't map on to human affairs very well. No matter how cynical you may be about the current state of human affairs, we humans still don't end up looking like ants all that much, mainly because we have big brains and those big brains develop.

Sociobiology's notion of genetics is simply untenable to modern biology. In 1957 C.H. Waddington published a book called The Strategy of the Genes which set the pace for interpreting the interaction between genotype and environment in which the phenotype is produced. Few since that time have conceived of naive genetic determinism in any reasonable way. The phenotype must always be considered to be the product of an interaction between the genotype and the environment. There's always a developmental dimension to genetics, even for the simplest critters, and that understanding is not reflected in sociobiology. They wish to simplistically point to the genetic determinant of specific social facts, both in non-human and human social animals.

In opposition to sociobiology, biogenetic structuralism takes the view common to the neurosciences that the brain is the organ of behaviour - that's a quote directly out of many neurology textbooks. The brain produces behaviour. No account of behaviour that excludes an account of brain operations is complete. More than that, you'll never understand the development of behaviour, and where it originates, until you understand the neural structures producing the behaviour.

Q: You take the view that brain produces behaviour. Isn't your point of view directly opposite to phenomenology?

Edmund Husserl (1859-1938)

A: On the contrary, we embrace phenomenology, if by phenomenology you are referring to Husserlian (1931) transcendental phenomenology, and to some extent Ricoeurian (1962) hermeneutical phenomenology. Also, Merleau-Ponty's (1962) phenomenology of the body interests us to some extent. But I will specifically get into phenomenology in a later lecture. There's a phenomenology to knowing the brain, just as there is a phenomenology to knowing behaviour, or a phenomenology to knowing other, more subtle aspects of consciousness directly. Another way to put it is there is a phenomenological element to any knowing, regardless of the intentionality, or the mindstates in which the knowing is occurring. There is a phenomenology possible, regardless of the object as "transcendental guide" to exploration and knowledge. There is the possibility of phenomenological reduction regardless of whether the object of consciousness is the brain, thoughts about the brain, thoughts about the thoughts about the brain and so on. The brain is not some objective reality, some Kantian neumenon, to which social behaviour or experience is positivistically reduced. We refuse to be baited by reductionist constructs (see Rubinstein et al. 1984). There is a phenomenological ground for understanding all knowing, including knowing about the brain, and that phenomenology is precisely available via the Husserlian epoche.

C.S. Peirce (1839-1914)

In a Peircian frame (see Almeder 1980), all knowledge is fallible and hence incomplete, partial, regardless of whether the knowledge is about the brain or about consciousness or about red tomahawks and green tomahawks in Highland New Guinea, or shamanic dances among the Kwakutl. We agree with Husserl that certain intractable problems in science will remain insoluble until individual scientists perform the phenomenological reduction. Part of the problem I face in the course of these lectures is moving from the notions about brain that we have developed, to an acceptance of phenomenology, and an argument for the necessity of the phenomenological reduction. It's not easy for people to see why the whole move to phenomenology is necessary, even for those who have been acquainted with biogenetic structuralism quite a while. And that's part of the intention of this reflection upon the biogenetic structural project - to clarify that movement to phenomenology. But I'm getting side-tracked here!

Francisco Varela and Humberto Maturana

Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela have proposed a theory of "autopoiesis" in biology to account for the apparent autonomy of organisms vis a vis their environment (Maturana and Varela 1980, Varela 1979). They persuasively resist the all-too-common computer analogy for neurocognitive activity - that being the view that brains lift "information" from the environment and produce "representations" of the world. Rather, they see the organism, and the nervous system within the organism, as autonomous, self-creating, self-regulating~ self-organizing systems. Their internally constituted, closed systems of knowledge are at best isomorphic with the environment, and are in no sense a copy of the environment - never a representative "map" passively received from the environment. Their conception of the role of cognition in biology is quite compatible with our notion of neurognosis. It emphasizes the structural invariance of principles by which the brain constitutes its cognized world.

Jean Piaget

Among the evolutionary structuralists~ the work of Jean Piaget (1971, 1977) stands out. You should understand that Piaget died in his eighties, and he published his first paper on mollusks when he was twelve years old. So we're talking about many decades of work during which the man steadfastly refused to waste his time - that was his attitude - systematizing or bringing closure to his point of view. Like the later C.G. Jung, Piaget's was a life-long project – an open system of theory, continually evolving and changing. The closest he ever came to formulating a systematic view of his project was Biology and Knowledge (1971). The book is very hard slogging, and there are two subsequent volumes (1977, 1980). Piaget began to turn on to his project when he had a job marking intelligence tests and, unlike anyone previously, he began to notice that the errors made by students were patterned. He noticed that errors in the intelligence tests were not random, but organized, and he asked why. He began to formulate the idea that maybe they weren't so much errors as they were distortions projected by the structures of knowledge in place at any particular developmental level. He originally tested this notions on his own children. That was the first phase of Piaget's research. It's the one most American scholars know about, and he is often criticized as having developed a whole developmental system out of research with his own three kids. This isn't true. He went on to found an institute in Geneva and studied thousands of children of all ages and diverse cultural backgrounds and has had considerable assistance from all sorts of researchers that came to the institute. What is really awesome about Piaget is that throughout his whole career he followed one question, and that question was "How did we evolve to know what we know?" How did knowledge emerge in human evolution? He's perfectly clear that the process of knowing is a biological process. He wasn't trained in the neurosciences, and he specifically said he would leave the neurological account to others.

Because he was not grounded in the neurosciences. Piaget made certain mistakes. For example. he claims that structures don't develop until action develops. His "schemes" develop out of what he called the sensorimotor stage of knowledge. He held fast to the notion that a child cannot know until it can act upon something. Now, there's plenty of evidence that the situation is more complex than this, particularly when considering the development of neural models within the visual system. Because of his theoretical assumptions, he developed no methods that would get at – say, a motor-wise immature, but visually precocious human infant. There's a whole field in contemporary psychology that you might call the psychology of the competent infant (see Stone et al. 1973). This psychology is pushing our understanding of infant competence earlier and earlier. back into the womb and towards conception, and can only be accounted for by reference to the degree of neurological development in pre- and perinatal life. It's becoming clear that although it looks behaviourally rather passive, the infant is neurologically and cognitively very active, particularly for the first six months post-partum, and before that in the womb.

Karl Pribram George Miller

The holographic paradigm of Karl Pribram (1971) is another example of an evolutionary structuralist perspective of interest to us. He is a neuropsychologist who worked with George Miller (see Miller et al. 1960) – one of the great geniuses of psychology. They developed an understanding of how much of human knowledge is based upon the capacity of the neural system to chunk information, and lay it out in temporal sequences, or "plans". You may notice if you look at Biogenetic Structuralism that we've talked about holographic models. We, like Pribram, were entranced by the then new developments in laser photography, and the metaphorical similarities between the type of information processing that is possible in a hologram and what appears to be the case for the human brain. So we borrowed that metaphor from the same place that Pribram did. The difference is that Pribram really does believe that the brain is a hologram, operating on holographic principles, and we don't and never did. So, after Biogenetic Structuralism , we dropped that metaphor entirely, and it never appears again in our work. We do however retain the notion of neural model. Model and modeling are central to our work. We continue to speak about neurognosis, or neurognostic models, but we left holography behind.

Q: You are, then, concerned with the interaction between the womb environment and the neonate?

A: You mean like Gregory Bateson's notion of an ecology of mind? Yes. The brain, as the organ of behaviour, has as its primary function the adaptation of the organism to its environment. This primary function, as we shall see later, involves a fundamental intentional polarity between subject and object, both of which are constituted in the brain.

Q: That would be a little more useful than a holographic metaphor?

A: Absolutely! If you read Biogenetic Structuralism you'll see that we're attracted by the idea of information being stored in a form that doesn't actually look like the information. Holography, as you will know, blends two forms of light, and the interference pattern that is produced by the blending is what is recorded on the emulsion. As a consequence, you could chop up the hologram into fifteen pieces and you would still have fifteen whole images. But you also get a loss of detail and information in each fragment, even though you get a total pattern. Why that is so attractive as a metaphor is because the brain operates in such a way that it has a lot of redundant circuitry, so that you can't find a place where you can cut out a particular memory – like your mother's face -- and leave everything else intact. You've got this model of Mom, but you can't find a place where you can pull Mom out and not disturb all the rest. That was a localizationist notion that was entertained in the neurosciences once upon a time: one locus, one memory. But we now know the brain doesn't work like that. It works something like a hologram in recording information over wide areas of cortical and subcortical structures. On the other hand, the brain can be damaged, and it will produce deficits, but they're not particular deficits like you lose only Mom's name and not Dad's, or whathaveyou. The general ability to sequence activities in a coherent plan may be lost because of frontal lobe damage.

These are but a few of the main themes in evolutionary structuralism; themes and perspectives largely ignored by anthropologists. Structuralism for most anthropologists is equated with the works of Levi-Strauss, Jacques Lacan and Roland Barthes. If you look at semiological structural theories carefully you will discover that they all lead to exegetical methods. In exegesis you take a text, usually some form of observable like myths, and you track the similarities, the relations between elements, and you deduce the structure that produced them. You don't need anything but the text and certain formulae or techniques. You don't have to look at the individual who spoke the text, nor often even the cultural context. If you want a critique of that point of view, look at Clifford Geertz (1983), or Paul Ricoeur (1967, 1968). Though by no stretch of the imagination evolutionary structuralists, they put that one to bed really well, showing that any ritual is embedded in a semiological context - an entire symbol system which has to be taken as a frame of reference or you miss a lot of information, or distort the view depicted in the ritual. One of the many weaknesses of any exegetical method is just why accept one interpretation and not another that somebody else may deduce to account for the observables. Why is Levi-Strauss' analysis of myth any more compelling than John Cove's? Or mine? Or yours?

Q: Is the point really which account is the most useful?

A: Not really. The question one raises is how do you determine the truth value of the one deduction over the other. Is there any independent data base that you can look at, any body of evidence independent of the exegesis itself, that can confirm or disconfirm the truth value of the interpretation you've deduced? In evolutionary structuralism, particularly in biogenetic structuralism, you are forced by the assumptions of the paradigm to go to another data base and make sure it's in accord with your model. If it's not in accord, then your model is faulty. If you presume that the only organ that produces myth is the brain, and that myth-telling, or creation of myth is somehow a product of brain function, then there has to be consonance between the two views. If there isn't, then your model is incomplete. You've missed the mark somehow.

HOMO GESTALT

We take a rather controversial view that cultural humanity is in fact a passing phase in the homination process; a process that leads us from a more or less pre-cultural primate adaptation, heavily determined by genetical information processing and behaviour, through a phase of increasing reliance upon adaptation through flexibility in the construction of socially constrained and transmitted points of view. The phase of cultural adaptation will in turn give way to a post-cultural phase of adaptation which will be carried out by a sentient being - our evolutionary successor if you will - capable of routine cognition that transcends cultural points of view. We have called our evolutionary successor Homo gestalt (see Laughlin and Richardson 1986). We borrowed that term from Theodore Sturgeon's wonderful science fiction novel More Than Human (1975).

More Than Human

by Theodore Sturgeon

Our extrapolations are based upon modern biological principles discussed very nicely by Steven J. Gould in his work, Ontogeny and Phylogeny (1977). Particularly important is the process of neoteny. What we understand to be an adult cultural consciousness in Homo gestalt becomes truncated, squished, and pushed back in development to become a sort of adolescence in the development of adult Homo gestalt consciousness. So in the future maturation of hominid consciousness, what we call "man the culture-bearer" will be a developmentally brief phase of adaptation -- a sort of "kid the culture-bearer". It will be passed through much more quickly and form a premature stage prior to the emergence of a higher developmental phase. What adult Homo gestalt consciousness will be like is only suggested in a handful of human beings today who reach a form of transcendental consciousness in which the brain is capable of adapting to its environment, at will, without reference to fixed and received points of view. Such a consciousness can entertain all points of view, or no point of view at all - it can just track what is.

Q: A cognitive level that is consummately aware of what perceptual pictures are operating and can shift them or transcend them. If culture is like a perceptual filter, then we don't "see" because it's always there.

Q2: Would this Homo gestalt , or his emergence, coincide with a redundancy of the body?

A: You are presuming in your question that we understand what the body is, that the body is a given rather than a problematic? Is there a body? And what is the difference between the cognized and the operational body?

Q2: Well, I use it interchangeably with culture.

A: Well, maybe the body of your perception is a point of view on yourself, and if you follow me there, then I think quite rightly, yes. The conception and the experience of the body will be quite different. There won't be anything like a little orb of radiant consciousness floating in a sort of Star Trekian plastic sphere, speaking through tubes in the wall. This kind of fictional, disembodied spirit is just another projection of western mind/body dualism, which we altogether reject. Useless for science, and science didn't develop it in the first place. Mind/body dualism is a pre-scientific mode of knowing, a heritage of this culture, a part of the "natural attitude" of Euroamerican understanding, as Husserl would say.

Q: I'm not quite clear what you're getting at. Can you elaborate?

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

A: It might make better sense if you look at it as did Merleau-Ponty. A basic dichotomy is presented by our experience of body - if I reach out and touch my own hand, and if I put my awareness there, I can see that I may experience the body from the outside-in, or from the inside-cut, just by shifting awareness. One can be in this hand feeling, or in the other one being felt. Merleau-Ponty (1962) did not seem to realize that there is a neurobiology to this dichotomy. The sensory system is designed so that it distinguishes detection of internal events from the detection of external events. The neural system is pre-adapted to distinguish what's happening within itself ("interoception") and what is happening outside itself ("exteroception") - it's very adaptive to be able to do that.

Let us proceed with Wittgenstein's wisdom: if it can be said it can be said clearly, if it cannot be said, it must be passed over in silence. And ultimately that dictum can apply to anything that can be experienced. There is an ineffability to any experience. Language did not evolve to replace direct experience, but to augment it. That's a hint of the kind of past-cultural consciousness that our evolutionary successor will have, supposing we don't blow it before we get there.

Q: The cultural adaptation that you referred to as being flexible in points of view -- does it only occur in Homo gestalt as a culmination?

A: It's not a culmination. It's the next phase in the homination process, the sentientization process, the unfolding of consciousness which is going on all over the universe, I'm quite sure. I think we are on fairly solid ground making certain extrapolations by looking back at the trajectory of the development of consciousness on this planet and projecting a bit into the future. I'll be more radical than that - I don't think we're in the middle of the cultural phase at all, I think we're approaching it's end, and the evolutionary transformation is accelerating very fast. I can ground that claim in a lot of data. We're speaking here of the orthogenetic dimension. The emergence of sentience in the universe is not random, but lawful. As we argue in biogenetic structuralism, there is an orthogenesis to the evolution of brain and hence consciousness. Also, as we argue in Brain, Symbol and Experience , from a certain technical point of view, it's not function that evolves, it's structure. Evolution really depends upon changing the structural aspect of things. So, in a certain sense, it is brain that evolves and not behaviour. They're inseparable, of course. If you don't keep the structure in mind, you run into certain methodological problems, such as being clear about the locus for the evolutionary change, because as Piaget pointed out, different structures can produce the same behaviour. You can have a very stupid system and a very smart system producing the same action. How do you distinguish the one from the other if you only pay attention to function or action? You want to say that one is more advanced than the other – that it is evolutionarily more developed.

Q: Wouldn't a more advanced structure be able to display a wider spectrum of behaviours? So, although you can't measure structure simply by behaviour, spectrums of behaviour can measure range of structural flexibility?

A: Yup. And the complexity of the organization of serial behaviours into plans. For example, a chimpanzee is quite capable at a very early age of deciding it's hungry, going off into the woods, looking for just the right branch, preparing it just the right way, coming back to the termite hill, licking it, sticking it in, waiting until the bugs get all over it, pulling it out and eating the tasty little critters. Baboons who are living in the same operational space and who also like to eat termites, will wait for them to crawl out of the hole to lick them up. They apparently can't learn that they can put together a serial progression of actions with some intended purpose thirty minutes down the line. Baboons are boxed into a spatiotemporally limited cognized environment relative to the cognitive powers of your average chimpanzee. I am giving this loose rendition of the model to show that biogenetic structuralism is an evolutionary perspective that treats the stuff of modern cultural anthropology as but one locus for the study of the homination process. In no sense should we treat Homo sapiens as the end product, which we unconsciously tend to do. Very little anthropology talks about the future of society and consciousness. By the way, the transformation that becomes Homo gestalt will have social implications, but what we mean by society will naturally change. I don't want to get too far into this other than to emphasize that the central question that will underlie all of these lectures will be the question of the evolution of freedom. But I will here only suggest questions, point directions. What is freedom? Freedom from what? Freedom to do what? What is the relationship between freedom and the development of the biology of the organism?

Q: The question arises, in talking of this, how do we learn to transcend? Can we change the structure of learning?

A: Yes. As we note in the future of human consciousness paper (see Laughlin and Richardson 1986), there is really no such thing as Homo gestalt , and there is no such thing as Homo sapiens , either. There is a homination process, and in so far as we transcend - that is, in so far as we operate in our own lives to transcend cultural points of view - we are Homo gestalt becoming! This is in perfect keeping with modern biology in which it is clear that phylogenesis is realized in ontogenesis; there is no phylogenesis, there is just beings developing and passing on their genes.

Q: Your scheme that embodies the distinction between past, present and future - wouldn't it be simpler to say that there is just one moment, now, and to explain this ontogenesis in terms of now-ness, instead of putting it into a scheme which tends to escape the real impact of totality - also that Homo gestalt is here now insofar as we accept it?

A: Nice! This is why we're led to consider something on the order of a Sheldrakian (1981) "morphogenetic field", or better from my point of view, a Bohmian (1980) "implicate order", in which all moments are present. Bohm's view is that the phenomenal presence is an unfolding and enfolding process out of the implicate order - the latter being a totality, an energy field, if you will, that is implicate in the universe, and not explicate. The unfolding and enfolding of phenomenal reality is the explicate order which appears to pass like a wave of nows, but to exhibit an order that we can know. All the possible orders are present in the implicate order. all simultaneously present. It makes no sense to talk about time in the implicate order - time only has a referent in the explicate order.

Next time we get together I will talk about the traps to clear thinking that we have hoped to avoid by pursuing the biogenetic structural project. We have been quite concerned with the entrapment of thought made easy in the culture of science – thus preventing clear observation and creative thinking. Because we have consciously tried to avoid these traps, we have been led to some of the more peculiar, controversial, and more difficult to grasp formulations in biogenetic structural theory.

Move on to Chapter 2